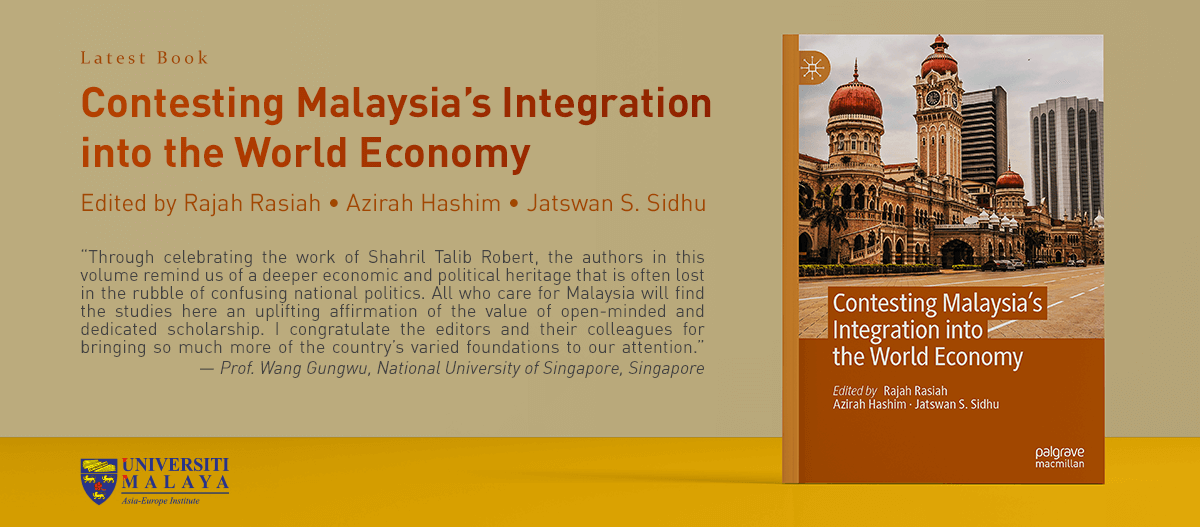

Contesting Malaysia’s Integration into the World Economy

Edited by Rajah Rasiah, Azirah Hashim and Jaswant Sidhu

A Book Review

“Show me the book the man reads, I will proceed to show you the man,” affirmed George Bernard Shaw. While there is much truism to what Shaw may have once said, “Contesting Malaysia’s Integration into the World Economy,” as edited by Rajah Rasiah, Azirah Hashim and Jaswant Sidhu, all of whom had been at the helm of the Asia Europe Institute (AEI) in University Malaya, there is something even truer.

Show me the man or/and woman who inspires the other, one can show you how knowledge is built from the ground up. Despite the pedigree of all the authors, the attempt to understand “peasant studies,” indeed, the poor and deprived, was redolent in most, if not, all of the chapter. Even more importantly, was to understand how some Malay/Malaysian scholars had understood the “everyday struggle of the people,” even prior to the delightful scholarship of James Scott in 1995, with tangential mention of the “art of the resistance” also by the same author at Yale University.

Divided into the expertise of 17 different scholars, all of whom are some of the best minds in Malaysia, all the contributors were, in a way, taking up the challenge of the late Professor Shahril Talib Robert, who called for serious, in turn, systematic, “historical interrogation.”

In and across every single page of the book, that spirit of inquiry stayed true with each and every contributor.

But unlike the Cambridge approach of Professor Quentin Skinner, both of whom sought to unearth the origin behind each idea, especially, the rise of realism in international relations, “Contesting Malaysia’s Integration Into the World Economy,” is undoubtedly different. Even surprisingly deeper.

While Skinner and Bew found “realism,” to be an idea rooted in the statecraft of Otto Von Bismarck, the Iron Chancellor that signed various seen and unveriable agreements with all the powers in continental Europe, often without a care of their impact, other than to solve an issue that was focused principally on the quest for a greater Prussia in terms of size and power, “Contesting Malaysia’s Integration Into World Economy,” went deeper.

It is a brilliantly edited book about colonial knowledge passed down from two of the four generations of social anthropologists in Malaya/Malaysia, of which the first two generations were in the main, colonial scholars cum administrators.

However, the full rendition of this book was not a rancorous outcry of victimization, especially by the colonial powers, although principally the British, it was an honest explanation of how Malayans, subsequently, Malaysians, knew now to activate their own agency.

As Chapter 1 observes: “This book focusses on issues that are largely confined to colonial history, issues that connect pre- colonial developments that have their origins in colonial rule in Malaya. In doing so, the prime thread that ties each of the chapters, was the use of novel interpretations to rethink these issues.”

Thus in contrast to the Cambridge method of understanding the history of an idea, often tracing it to a place or a person who espouses it in a unique way, this book was full of colorful vignettes and statistical samples of what made Malaya and Malaysia unique unto itself.

Take Chapter Two, ‘Revisiting Colonial Industrialization in Malaya,’ by Rajah Rasiah. The whole chapter was filled with actual studies of various forms of technology and manufacturing, light or heavy, that were deployed in a variety of economic productions (page 15 to 39).

Even the Japanese Imperial Administration of Malaya in 1941-1945, was not all blood and gore only, marked by a massive drop in light industry sectors, “the Japanese colonial government introduced more comprehensive central control than the British, whereby the sale of essential goods was regulated and a Five Year Production Plan was introduced in 1943.”

Elsewhere quoting Sultan Nazrin Shah, Rajah Rasiah explained how the work of His Royal Highness in Perak was able to outline the dawn of “free wage labor,” in Malaya (page 29).

The British all along had harboured the goal of turning Malaysia into an industrial hub.

Only that it safeguarded the interest of the British first, although the principal author who carefully explained this thesis i.e. Processor Jomo Sundaram was not included in the volume.

Chapter 3 by the late Zawawi lbrahim is literally neck deep with all the current scholars’ affiliation with two British social anthropologists Raymond Firth and Michael Swift.

Spanning a period of “70 years,” Zawawi lbrahim tried to explain how the field of social anthropology, to some extent, the relationship of the main factors of production ought to be understood in Malaya/Malaysia before each of them was mediated by the arrival of other labor groups and ethnicities that formed the country.

Zawawi lbrahim’s serious forays into all key thinkers in Britain and Australia with the Malayan scholars, whom they jointly trained, could be read side-by-side with Chapter 7, 8 and 9 in particular.

Chapter 9 by Danny Wong Tze Ken, for instance, delved into the history of the Hakka Community in Sabah. While the original roots of the Hakka Community in mainland China remain mythical to this very day, it was remarkable to see this chapter going into the Hakka Community’s relationship with the Church of Basel in Switzerland.

In turn, how some Hakkas in mainland China could have moved to Sabah in the 1850s when their charismatic leader Hong Xi Guan failed in launching a massive peasant rebellion against the Manchu Dynasty.

Chapter 7 and 8 by Sivarajachandralingam Sunda Raja and Viswanathan Selvaratnam, on the roles of the Malay aristocrats and Southern Indian Coolies in Malaya/Malaysia could not possibly be understood without understanding the collective scholarship of Shaharil Talib, Syed Husin Ali, AB Shamsul, Zawawi Ibrahim and a lineage of knowledge passed down by Raymond Firth and Michael Swift, if not Victor King too.

Bunn Negara at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS Malaysia) once remarked that editing a book is easy. He was referring to all the papers presented in the annual Asian Pacific Roundtable.

In the case of “Contesting Malaysia’s Integration into the World Economy,” which was prefaced by the foreword of His Royal Highness Sultan Azlan Shah in November 2020, in the midst of a lock down, where Malaysia was under the attack of Covid 19 not unlike other countries in many parts of the world, such a collective endeavor can only be extremely challenging to both the editors and all other authors; even if they could exchange their drafts online or over countless meetings in Zoom.

While this review stopped short of going into all chapters, it is worth mentioning that the Malaysian economy was deeply affected by the Great Depression in 1929 to 1935 in the United States (US) too.

Benjamin Bernake and Janet Yellen remain two of the aging economists in the US to have served in the Obama and Biden Administration.

Somehow, with the help of G 20, in 2008-2009, the world managed to pull through from a serious global financial catastrophe. Some banks were too “huge to fail and too big to jail.”

“Capitalism” as Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff at the Department of Economics of Harvard University is peppered with more than 150 years of peaks and valleys. As and when it fails, the politics can turn nasty, brutish and ugly.

Only when scholars learn how to work across regions and disciplines can the policy makers somewhat grasp the attendant problem of unfettered free market capitalism.

While the academic contribution to the field of social anthropology and policy studies of contemporary Japan was no prominently featured, there was a time when Malaysian thinkers could not progress further without a stint at the Center of Southeast Asian Studies at Kyoto University.

A place where Professor Osman Bakar and Professor AB Shamsul were most familiar with in addition to Cornell University, if not Yale University and University of California in Berkeley too.

This book’s three editors deserve all the highest compliments, not excluding Maznah Mohammad and Johan Saravanamuttu’s, both of whom had done their fair share to keep Malay and Malaysian studies well grounded, with the latter on foreign policy.

In a post Cold War order that Akhbar Ahmed at American University in Washington DC warned is slowly morphing into a “pre War” period of World War I and II—-where 2024 alone, has witnessed more conflicts than ever since 1945—–the attention should shift to non- exclusionary and non- rivalrous Global Public Goods, which Japan, especially the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is clearly rooting for.

As the Chair of ASEAN in 2025, Malaysia should work closely with JICA, indeed, the Korean International Cooperation Agency (KICA) and TIKA (Turkish International Cooperation Agency) too. All and sundry should collectively fight for a better world ; without which the international system would be fraught with protectionism and dumping of goods all over the Global South.

The latter is due to the over capacity of China given the tariff walls erected against it in the US and the UK.

Due to the lackluster economic performance of China, that could last for decades, especially when its property glut cannot be resolved, coupled with a strong fiscal stimulus program by the Chinese Central Bank, the effects across Southeast Asia writ large on the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMM) could be devastating .